By Joanna Radin ( Yale University)

“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark”

– Hamlet, William Shakespeare, Act I, Scene IV

In the Western intellectual tradition rot has a negative valence. It is associated with waste; what is no longer capable of being saved. To be rotten can be a material state—a fruit past its prime; a moral state—a disfigurement of the soul; or a social state—a corruption of power.

Rotting activates and offends our senses. It feels slimy. It tastes—at least to a human—like something to be avoided. It reeks of death. The science that studies decomposition is known as taphonomy, which comes from the Greek, meaning tomb. Yet, as Astrid Schrader has argued in the case of algae blooms, “Dead zones [created by such blooms] are not dead at all—in fact they are full of life—just not the kind of life we want.” Interpreting Bataille, Achille Mbembe has argued: “Life is defective only when death has taken it hostage. Life itself exists only in bursts and in exchange with death. Death is the putrefaction of life, the stench that is at once the source and the repulsive condition of life.” In Hamlet, the decomposition of the King both physically and politically is what allows all that is repulsive or rotten to be revealed and reckoned with.

Processes of putrefaction are powerfully generative. They provide epistemologically rich opportunities to conjure multispecies worlds and with them alternate visions for what it means to be alive. Rot is a way of thinking ontologically in reverse. It can mean understanding the order of things as they disappear rather than as they come into being. Rotting is a process that requires collectivity – from the vulture to the microbe – the scavengers and decomposers who assemble to help metabolize life after life. What we are wont to identify as “nature” renews as it undoes composition.

Biotic materials such as excrement or even entrails experience afterlives when recognized as milieu for microbes and other organisms. In some circumstances, maggot-like fly larvae appear. They are not spontaneously generated but opportunists par excellence, always close at hand, waiting for their turn on the stage. The role played by such actors in the drama of rot has been made legible, in turn, through human uses such as forensic scientists who have been able to calibrate the debut of maggots to the moment between the end of life and the beginning of death. There are also circumstances in which non-human others’ ability to decompose is actively cultivated. Here, I’m thinking of the dermestid beetle’s long-running gig at the natural history museum, where nothing has managed to upstage its ability to strip bones of tenacious bits of flesh.

Dermestid beetles being used to clean a human skull at Skulls Unlimited International, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

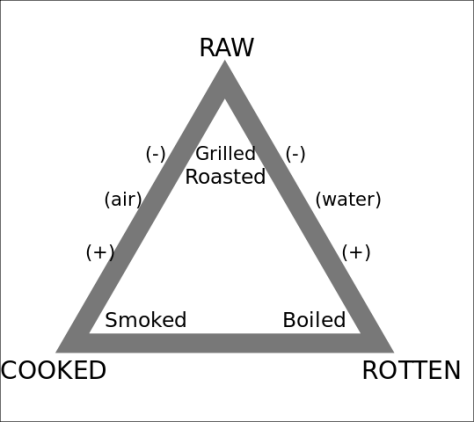

Sniff around and find rot at home in the human sciences, as well. Consider anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss’s “culinary triangle.”

Lévi-Strauss’s culinary triangle

This menagerie incorporates the category of “rotted” into his original and better-known binary of the raw and the cooked. Recently, anthropologist Tom Boellstorf has mobilized the culinary triangle to argue that paying attention to rot allows us to consider that the chef may not always be human. In this sense, rotting makes space for interpreting what is experienced as unplanned, unexpected, accidental, or even metaphysical. Non-human chefs, like yeast, transform rotting fruit or grain to become alcohol. In fermentation, the last gasps of plant lives are renewed by the respiration of microbial ones, creating a heady brew—sometimes accepted as the blood of Jesus, sometimes used to clean wounds.

Things are rotten everywhere. And that’s a good thing because there’s no dying or living without rot.

Further Reading

Boellstorff, Tom. 2013. “Making big data, in theory”. First Monday, 18(10).

Lévi-Strauss, Claude; Peter Brooks (tr.) 1966. “The Culinary Triangle”. In The Partisan Review 33: 586–96.

Mbembe, Achille. 2003. “Necropolitics”. Public Culture, 15(1), 11-40.

Schrader, Astrid.2011. “The Time of Slime: Anthropocentrism in Harmful Algal Research”. Environmental Philosophy, 9(1), 71-94.

Todd, Zoe. 2014. “An Indigenous Feminist’s take on the Ontological Turn: ‘ontology’ is just another word for colonialism”. Accessed October 2014. zoeandthecity.wordpress.com/2014/10/24/an-indigenous-feminists-take-on-the-ontological-turn-ontology-is-just-another-word-for-colonialism/